As I outlined in the latter half of my last blog post, there’s a really fast way to tell how close two coordinates are on the earth. I later wrote an algorithm based on these “closeness” methods to determine if two addresses are the same, allowing a buffer zone, and even find subgroups of it. For example, if you were to hand this algorithm multiple names for only 2 addresses (A, B), it could group the names that go to address A together while determining that address B street names should also be grouped together. While a very interesting side project, eventually it had the same problem all projects have– it was complete.

Once it was finished, I found myself opening the source code to it, looking for a brief time, and closing it. There were no apparent bugs, it met all use cases required; yet I didn’t want to be done with it, and so it was in the back of my mind. What else can this do?

Saint Patrick’s day this year, I sat with a few friends at a local brewery (shout out to COTU), and it came to the forefront of my mind once more, but in a new light. Rather than asking what else it can learn about addresses, I realized that it didn’t have to apply to addresses at all.

Looking around the brewery, I saw the band on stage, and a small crowd in front of them. As I leaned forward, I started to look at the closeness of the people in the crowd– they weren’t evenly distributed as you would expect, giving everyone a fair space. Instead, you see people leaning together with their friends, even closer with those they love. One particular man, who clearly not as funny or sober as he thought, found himself with a lot of elbow room as people edged away from him. While Geomatch, my address comparison algorithm, could find the distance between I places on earth, I began to wonder if it could determine who is alone in a crowd of strangers.

For this, I needed an image of a crowd. A moment with google brought me to this image:

I particularly like it because it verified my suspicions– you can tell by looking at this that there are families in the crowd. Mothers holding children, fathers giving piggyback rides, friends leaning together to speak. Though the average density of the crowd is pretty uniform, there are subgroups here– which got my hopes up for Geomatch.

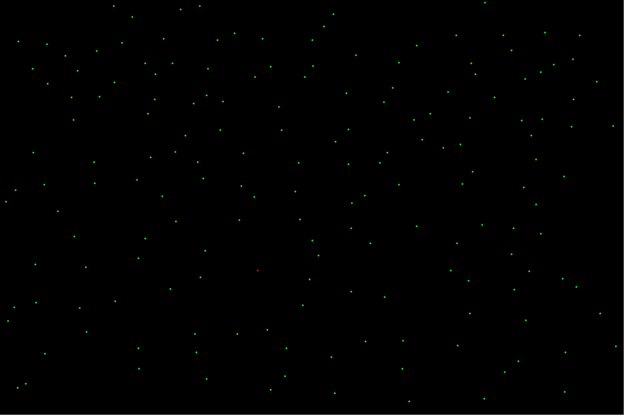

The first task was to feed this crowd into coordinates listing the location of each person… at the very least, a tedious task. Like all tedious tasks, I assigned it to my close friend and coworker Susannah Darling. She would work on facial recognition to be implemented later, while I simply used GIMP to add a green “+” to what I considered to be the top of everyone’s head– right behind the hairline. What I ended up with looked like this:

Looking at this, I immediately noticed a point that I hadn’t noticed before (despite drawing them all by hand). In the image above, I’ve marked it red for easy identification. This point has a lot of distance between him and everyone else, despite being in the middle of the crowd. What on earth is he doing?

Ah, the camera man. It would make sense that people would be respectful and give him space to shoot. It’s rather funny how respect and simply being uncomfortable can sometimes get the same response. This is a great data point though– he is alone in the crowd because he stepped out of it (while still in the middle of it), to do something that the majority of them weren’t. That’s human behavior 101. If I’m in a group of people talking about sports, I would step away from it to take a phone call or take a photo like he is. In this case, he’s stepped out of any subgroup he was in, distancing himself from those he knows, while still being in the crowd. Any algorithm I make, then, would have to mark him as an outlier in this image to be correct, and we see a potential new use case. Can we tell, more than who is here alone, but who is here doing something the rest of the crowd isn’t?

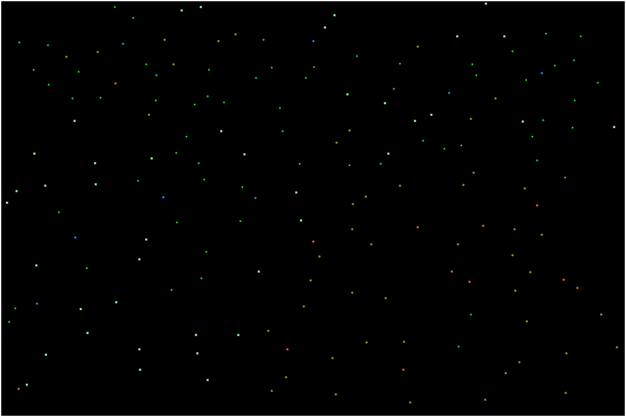

When I first tried it with Geomatch, it became immediately apparent that it was not currently up to the job.

I could go into detail about what each color means and why it chose these points for each color but I’d rather save us both time and say this instead; it’s wrong. So I fiddled with it over and over, playing with the origin’s definition, configuring the match distance to get different, equally wrong results. At one point, it managed to tell me there was more origins than subgroups (which is weird, since each subgroup by definition contains an origin), and at another it told me there were no origins at all, but there were matches to the origins that didn’t exist. Needless to say, I was very confused.

It was then that I remembered an old adage a favorite professor left me with; “If you aren’t getting the answers you want, perhaps you aren’t asking the right question.” You see, Geomatch was built on the principle that the addresses given to it would all be centered around the real physical location– the Origin point to which all other data points are compared. In a roughly evenly distributed crowd where no data point is weighted more heavily than others, there is no origins. Thus, in the image above, I learned what should have been obvious at the start: “Are these addresses synonymous” does not answer “is this person acting alone?”

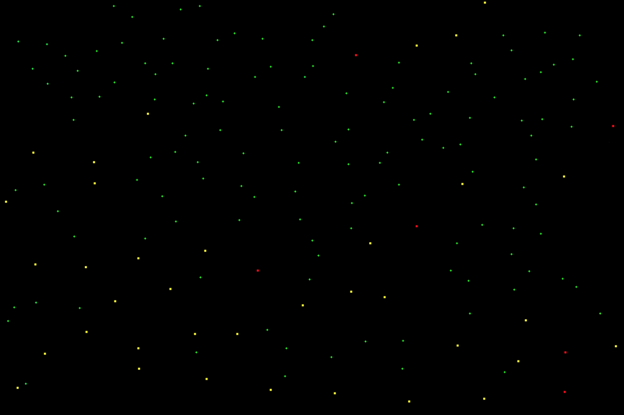

After decentralizing the algorithm so that it no longer required an Origin, I simply evaluated the question “how many points are within X distance of this point?” Two or more points near it will be green; 1 other matching point will be yellow, and no matching points are marked red.

And here we have it; those alone in a crowd of people. There’s a lot we can learn from this data point as well. In the US, we have seen hundreds of mass shootings in the year 2015 alone. We’ve seen suicide bombings in both Europe and the Middle East. Of these types of violence, the one committing the violence is often acting alone inside of a crowd of strangers. This is because, in order to cause the most casualties, they must spread themselves out into crowds of strangers. Now, this algorithm wouldn’t be able to tell you if a group contained someone with malicious intentions, but if you knew it did, it would certainly prioritize the people you need to investigate. In particular, the red dot to the north, who’s surrounded by green. That implies that there’s a stranger amongst people who otherwise are comfortable with each other’s presence; a high likelihood that he knows none of them. Coupled with the tighter density of the crowd there, it’s very well possible that he’s trying to position himself in such a way that will affect the most people.

Which brings me back to the point of this article; Never think of your project as done, especially not projects you’re passionate about. This has gone from saving someone from having to check two addresses on google maps to potentially saving lives. You never know what your algorithm can solve until you change the type of input it receives.

Comments