Amazon Web Services is capable of providing the infrastructure to run all of your applications and services just as if it were in your own datacenter. To make sure that their customers felt safe with this assertion AWS has gone to great lengths to isolate customers’ networks from one another and in doing so given their customers the tools to design, manage, and enhance their own network security via VPC (Virtual Private Clouds), subnet creation, custom routing tables, ACL’s, and Security Groups.

Amazon Web Services security groups are pretty straight forward. They are set up so that you can specify (for Inbound or Outbound access) a port and a source (or destination) that is allowed on a per interface basis. This of course can be expanded to a port range and a source(/destination) address range as well. This follows the firewalling models of old and supposing that you have your network model well defined and are creating machines in the correct subnets this is a good system for discriminating access to the services that your VMs offer. This classic approach could be referred to as Subnet Oriented Network Security. Meaning that services have access to other services based on their placement within the network (their subnet, or the target subnet).

With the introduction of microservices we are seeing an increasing breadth of services necessarily available on the same subnets. As the web of microservice interoperation becomes more complicated a more adaptive security model should be implemented that better enables the constantly changing needs of your applications while still retaining high levels of security.

Endpoint Categorization

The key feature that has enabled the ability to build an adaptive security model around your services is Endpoint Categorization. This is essentially the ability to target security groups with other security groups giving you the ability to categorize your security endpoints based on the service that they provide. Instead of needing to specify a CIDR block (IP Range) that a specific rule targets for permissions you can now target a security group by name meaning that any instance with that security group has that permission.

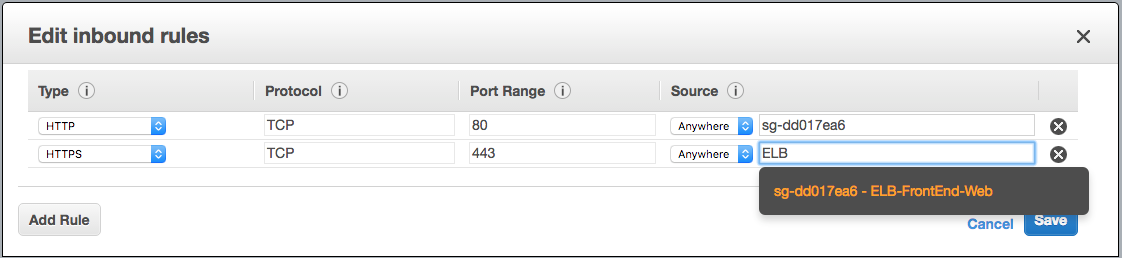

Image shows rules in the security group applied to the front end web instances, allowing only instances with the “ELB-FrontEnd-Web” security group to contact it on ports 80 and 443.

Image shows rules in the security group applied to the front end web instances, allowing only instances with the “ELB-FrontEnd-Web” security group to contact it on ports 80 and 443.

The ability to categorize your endpoints in this manner opens up a world of tighter security throughout your network transparent to your underlying network architecture. Taking advantage of this small feature can make a big difference in your security footprint (open ports per host).

Example

Let’s put together a full-stack example of what this would look like.

Software:

Let’s take a look at the software in use in our example:

- Nginx – Web Server: Will serve on port 80 (http) or port 443 (https) to web clients or other services (https://www.nginx.com/)

- Tomcat – Java Application Server: Manages and serves http based applications (http://tomcat.apache.org/)

- ELK – Elasticsearch, Logstash (+ FileBeat) , Kibana stack: This is a suite of applications that work together to provide log aggregation, facilitating the storage and searching / examination of your application and / or system logs. (https://www.elastic.co/webinars/introduction-elk-stack).

- Graphite – Monitoring, Graphing, Alerting platform: Graphite, StatsD, etc is a suite of software that can help you keep track of application and system metrics of importance to business and performance goals. (http://graphite.wikidot.com/).

- MySQL – RDBMS: MySQL has been around for a very long time, and continues to be a favorite of web programmers due to it’s ease of use, management and maintenance. (https://www.mysql.com/)

- ELB – Elastic Load Balancer: We will be using Amazon’s ELB service to distribute load.

Network Layout:

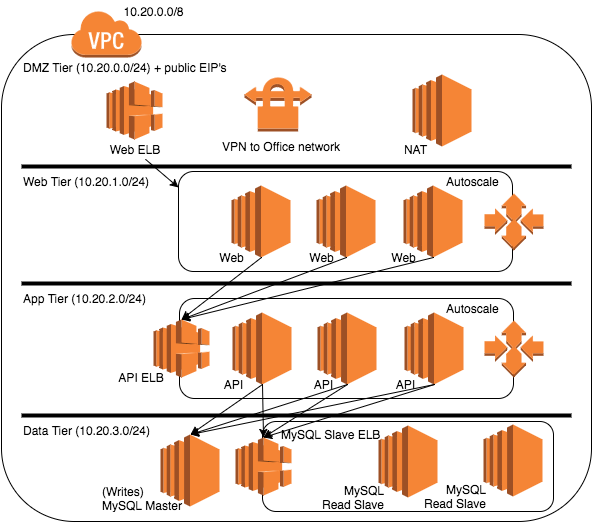

While we are focusing on service oriented security there may still be a number of things that fit a classic subnet security model. Let’s set up a classic 3-tiered subnet stack with the addition of a DMZ to further isolate internet access. Here is the network model for our application:

- Office Network CIDR: 10.10.0.0/16

- VPC CIDR: 10.20.0.0/16

- DMZ (private network with public IP’s assigned) CIDR: 10.20.0.0/24

- Web Tier CIDR: 10.20.1.0/24

- App Tier CIDR: 10.20.2.0/24

- Data Tier CIDR: 10.20.3.0/24

The DMZ Tier:

The DMZ tier is a place for only the things that absolutely have to be outward facing (publically facing). This includes: VPN endpoints, NAT instances, and public ELB’s. In this example assume we have all of these things. I’ll speak more about the ELB’s later.

The Web Tier:

The Web or front-end tier houses the services that generate the presentation of your application. This would usually be some dynamic web language and a web server (to provide security and speed to static resources). Just as an example let us suppose this stack consists of Nginx and PHP-FPM. Filebeat is running to push web, system and php logs to an ELK stack in the app tier.

The App Tier:

The App or middle tier holds the business logic of your application. In this case it is a Restful API coded in Java using JHipster 2 on Tomcat behind Nginx. Just like in the Web tier Filebeat runs locally to transport pertinent logs off to the ELK stack servers.

The Data Tier:

A MySQL cluster runs on the backend. As a note: the Data Tier is the only tier in this example where the nodes need to communicate with each other. Filebeat will transport the MySQL logs.

So the stage is set. Lets look at how all of the things in the these tiers interact:

The arrows in this graphic show only the flow of data for our application, but not for a number of things going on around it (logging, monitoring, etc.). In this tiered model, the rule should stand that every layer can only communicate with the layer directly above and with the layer directly below it. To this point the most important thing that we are doing is preventing the web tier from communicating directly with the data tier. This not only has the HUGE benefit of abstracting our data model via an API (the middle tier) but also preventing customer facing systems from having access to query level data architecturally preventing any kind of data injection or abuse.

Security Groups

Now that we know what our stack uses and how it’s laid out we will take a look at how to build out security groups.

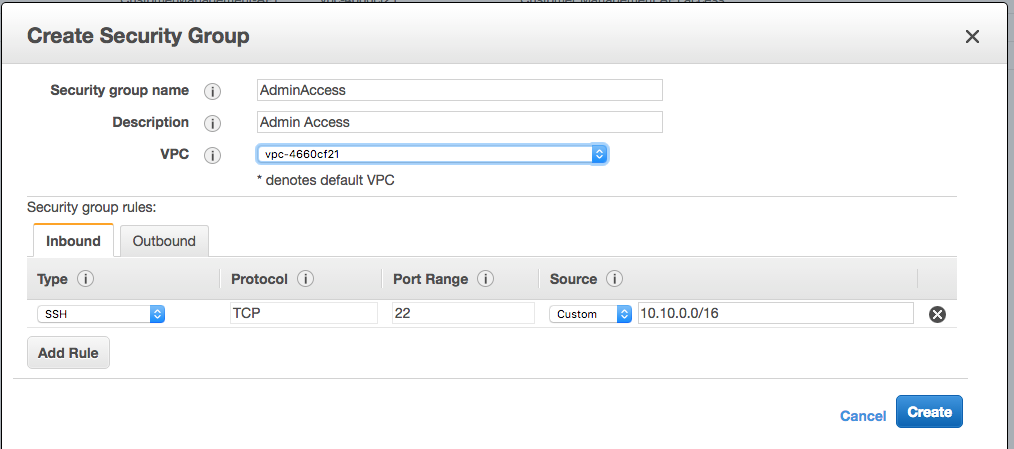

General Access

Firstly there are some resources hosted here that as an administrator or developer you are going to want access to. System access: port 22 for SSH will probably be about all you need. This entry is one of the few that will still have a target of an IP address, as opposed to targeting a security group due to the fact that this permission is going to be granted to the office network machines. Let’s take a look at the rule to add:

This will get your VPN / Office network access to the machines on your private network. Note: You do want to be VERY careful about who you give ssh access to. Construct this rule carefully to give access to the proper portions of your network.

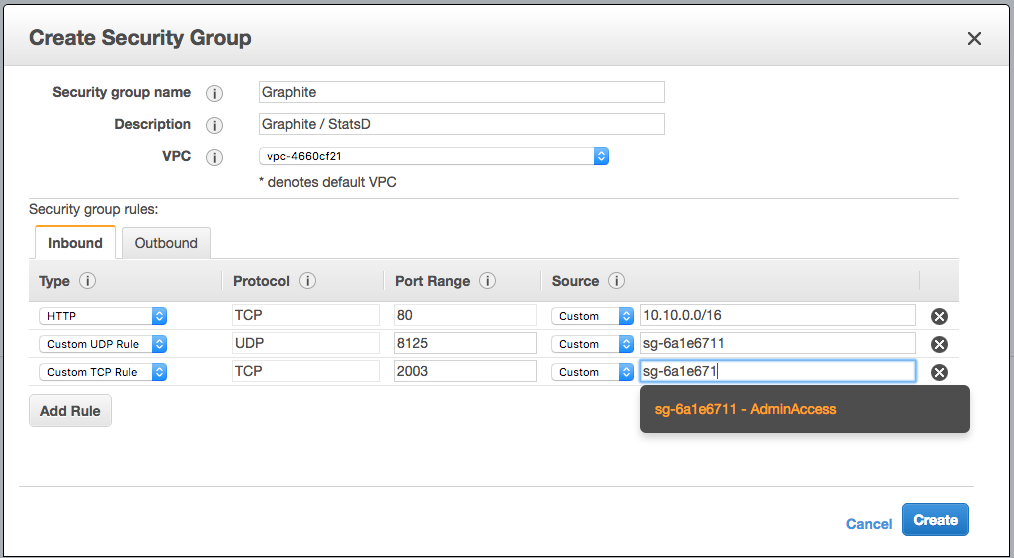

Next is Graphite. StatsD accepts UDP packets on 8125, and communicating directly with graphite (if you need to) will use port 2003. Since the display of this information will be accessed by office machines we will once again need a rule to allow that access as well. This will look like:

We are using the AdminAccess Security Group that we created above as the target for access to port 8125 (StatsD) and 2003 (Graphite) because all machines that will need to communicate with Graphite / StatsD will also have this AdminAccess Security Group. As we add new machines to the AdminAccess group, they will automagically gain access to communicate with instances in this group.

ELK – Very similarly, we will want to be able to access Kibana securely from our office network, and yet ensure that machines have access to deposit logs into ElasticSearch (assuming they are on the same instance).

Application Stack

Now we get into the meat of the situation but you have probably already guessed as to how this is going to go.

Starting with the outside facing ELB SG we are just going to allow port 80 and port 443 from everywhere since the point is to provide public access. We will call this “ELB-FrontEnd-Web”.

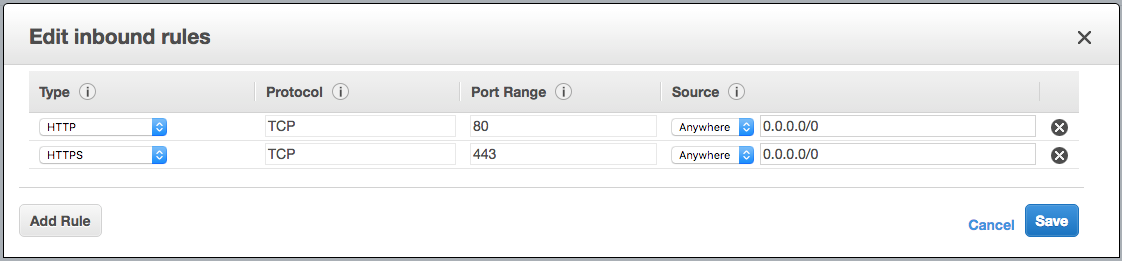

Inbound rules for the “ELB-FrontEnd-Web” Security Group.

Inbound rules for the “ELB-FrontEnd-Web” Security Group.

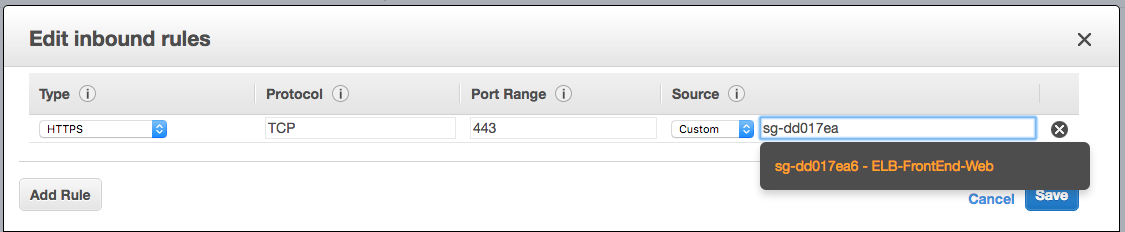

Moving on to the Web Tier, we will want to permit access to ELB we just set up. So adding a new group called “FrontEnd-Web” that will allow access to 443:

Inbound rules for the “FrontEnd-Web” Security Group.

Inbound rules for the “FrontEnd-Web” Security Group.

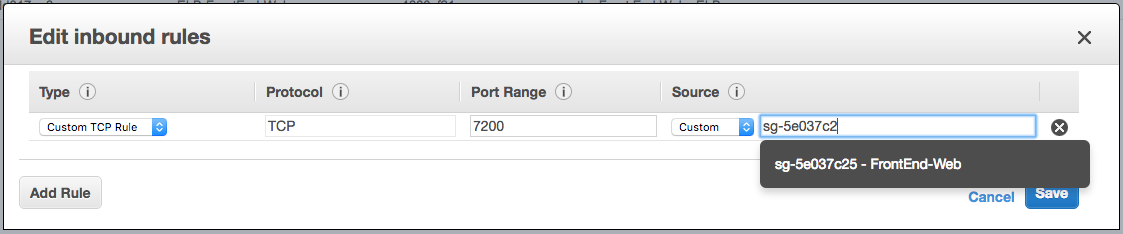

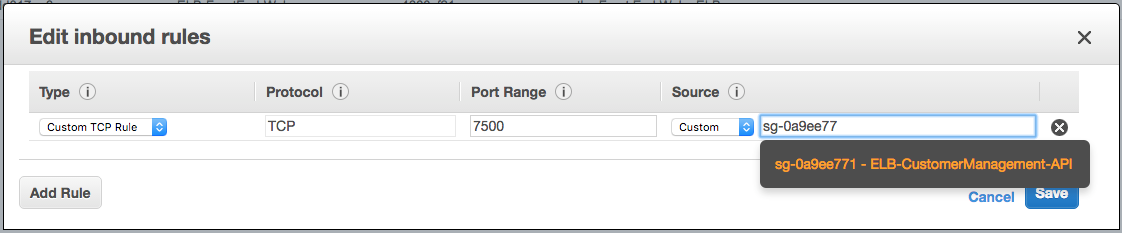

The App Tier ELB now needs to open up it’s own port 7200 for access from the FrontEnd-Web, called the “ELB-CustomerManagement-API”:

Inbound rules for the “ELB-CustomerManagement-API” Security Group.

Inbound rules for the “ELB-CustomerManagement-API” Security Group.

And now we need to allow the ELB to contact each of the API servers in the pool on port 7500 – “CustomerManagement-API”.

Inbound rules for the “CustomerManagement-API” Security Group.

Inbound rules for the “CustomerManagement-API” Security Group.

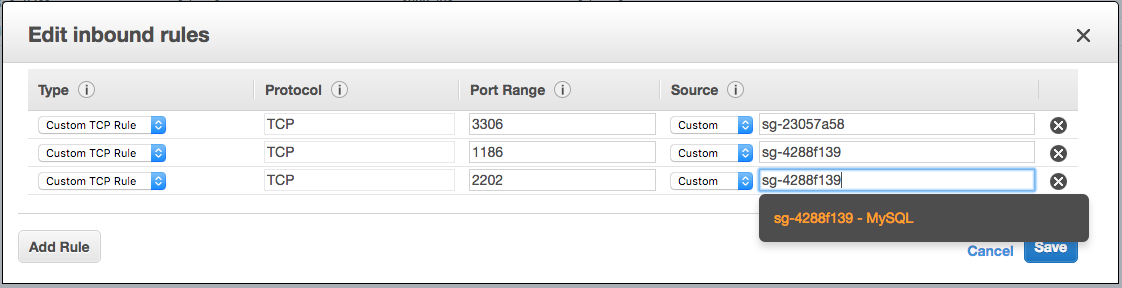

Lastly we grant the Customer Management API access to talk with MySQL on port 3306 – “MySQL”. MySQL will communicate amongst itself via ports 1186, and 2202 for clustering operations, so we need to allow those based on the assignment of the MySQL group.

And everything is chained together. Now our services are free to autoscale without fear of small network boundaries, or allowing access to non-relevant ports.

This example has been specific to Inbound Rules, but the same can be applied to Outbound rules you will just have to make exceptions for internet access if necessary. Note: You do not have to account for the use of ephemeral ports for Output access with security groups, as they remember connection state, however ACL’s do not and will need the ephemeral port range allowed.

Limits

Before beginning to implement and rely on this model it is important to consider AWS’s security group limits:

There is a soft limit of 500 Security Groups per VPC, this can be increased via a request or call in to AWS support. In most circumstances 500 will be plenty. Additionally there is a default limit of 50 rules per security group (50 Inbound and 50 Outbound). For Service Oriented Security, this is enough allowance, as there should really only be a handful of ports per service that need to be in use. Security groups are attached to network interfaces (in case you happen to have more than one network interface on a host). The default limit for attached security groups on a network interface is only 5. That small number can start to cause some issues.

AWS, in trying to be as welcoming to new users as possible, seemingly leaned towards more legacy network security, allowing room for LOTS of rules per group, and only a few group assignments per interface. The good news is that this issue is addressable.

The formula: (Security Group Rules) * (Groups Per Interface) = 250.

The default configuration: 50 rules per group * 5 groups per interface = 250.

You can request through AWS support a re-configuration of these resources, but there is a hard-limit at the product of 250 so you will only be able to change these 2 numbers on a scale. The most obvious next step is: 25 rules per group * 10 groups per interface = 250. This will allow you to assign 10 of these groups to an interface and these groups can have 25 rules apiece. If you need more still you could choose to drop down to 10 rules per group * 25 groups per interface = 250. So as a quick recap, the distribution of rules to groups can be assigned like this:

- 50 rules * 5 groups = 250 (Great for classic Subnet Based Security.)

- 25 rules * 10 groups = 250 (This should be adequate for most Service Oriented Security implementations to function correctly.)

- 10 rules * 25 groups = 250 (Security groups subscription should probably be automated at this level to alleviate management pains, 10 rules can be tight for some situations, but is still usually enough.)

- 5 rules * 50 groups = 250 (I’m not even sure AWS will actually do this for you. You should probably think about adding a VPC if you are approaching this need.)

Conclusion

Whether you are building for the future or migrating legacy apps it could be well worth it to your security footprint to map out the interdependencies of your application and plan for them with service oriented network security. Also it would be advised to devise a proper naming scheme for your security groups before getting started. This naming scheme should be descriptive, and include not only the service name or function but it’s point of application (i.e. ELB). Breaking security down in this manner is initially a bit of hard work (especially if you are migrating an existing application suite) but it can pay off in the long run relieving some maintenance and growth concerns while providing a tighter security footprint.

Comments