Applying the concepts of Data Meaningfulness and Usefulness.

One example given in the article [Data Usability by Susannah Darling](https://blog.ippon.tech/data-meaningfulness-and-usability-does-your-data-mean-what-it-says/) was that addresses should be stored as two Doubles representing a physical location (coordinates) rather than a String; let’s explore that further together.Comparing Strings: Why not to do this.

Suppose I had two users submitting the same address, 123 Main Street, and that the users have very little data validation at the user end, with the end result being the address stored as a String. 123 Main Street will obviously match with itself. With some fairly easy fuzzy logic, we can also make it match 123 main street or any other case. But suppose, further, that they had stored it as 123 Main St. This is far more difficult, as now we need to store a list of appropriate abbreviations for street, lane, place, boulevard, court, and more. Still doable, though.

Then it gets weird. 123 Main Street and Main Street 123 should be equivalent, so we’ll have to tokenize the string by spaces and check equivalence that way. As well, we need to decide if we should allow matching of addresses that contain zip codes to those that don’t, making the assumption that they’re talking about the same zip code. That’s not a huge stretch, as we’re already making that assumption when neither address has a zip code.

Then it gets impossible. Suppose, at some point, 123 Main street was 132 Broad street. Suppose 123 Main Street is at an intersection of streets and thus, is synonymous with 55 5th avenue. Suppose that there is even two names for the same street, like Main Street and Route 1. There is no way to compare these strings to get the correct answer– they are the same in everything but how the information is stored.

In this way, Darling has accurately described the data as lacking meaningfulness: how it is stored doesn’t accurately reflect the data it’s describing. If you can change the representation of the data (the String in this case) completely without changing the value of the information it represents (the location described), your data is not being stored meaningfully. Without a lookup, we can’t even know precisely where this location is; perhaps the only thing a location is supposed to tell us.

As well, she is right to point out the lack of usefulness of this storage method. We cannot compare these string addresses and get an answer. We cannot tell how far it is from other addresses. We cannot even tell if it is a valid address; at best we can tell if it looks like one.

Comparing Latitude and Longitude: Why it’s worth the API calls.

Suppose, when the two above users submit the same address again; 123 Main Street. This time, before storing the data, we’re going to do a Google Maps API call to get the latitude and longitude, then store it as two Doubles.

Well, now we know their physical locations. Doing a comparison for equivalence is as easy as two “==”s. We also get the benefit of being able to do a reverse lookup later to find it’s full address, and all synonymous addresses. The data unambiguously represents its own value perfectly; in other words, it’s perfectly meaningful.

A working example of added Data Usefulness

Here’s where the fun begins. Suppose we wanted to see exactly how far apart the two locations are. You could draw a simple right triangle given the line between the two points as the hypotenuse and use pythagorean’s theorem, but that’s too flat for Earth. Here’s a more fun method:

private static final int R = 6371000;

private static Double getDistance(Coordinate a, Coordinate b) {

double x = Math.toRadians(b.lng - a.lng) * Math.cos(Math.toRadians(a.lat + b.lat) / 2);

double y = Math.toRadians(b.lat - a.lat);

return Math.sqrt(x * x + y * y) * R;

}

Distance algorithm

This treats the two points as they are; two points on a sphere. R being the (rough) average radius of the Earth in meters, with Coordinate being an object type that simply contains a lng and lat– longitude and latitude. In short, this method works the same way as the pythagorean theorem, but is more accurate as it accounts for the curvature of the Earth. Note that a difference of 0.001 in the coordinates translates to roughly 111.2 meters.

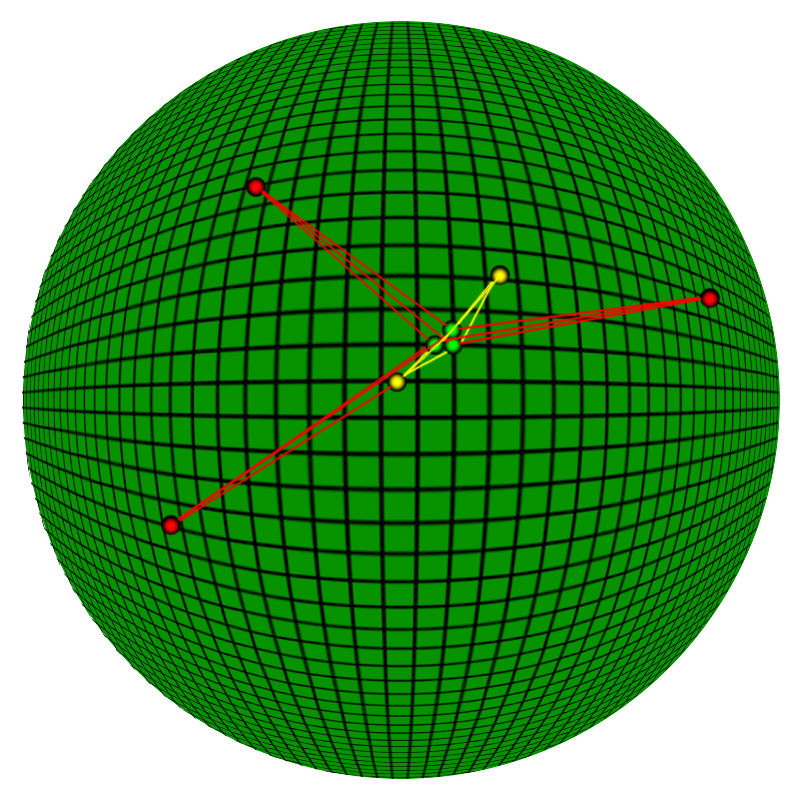

This is hard on your processors though; we both square and find the root of squares, with more math on the side, all to find the distance between two of the many points (each line on the image above would need to complete this whole algorithm). What if we wanted to find all points within a range, though? For example, if we only cared that the two things are within a certain distance of each other. We could find the exact distance and then find the result by comparing “actualDistance <= matchDistance”, or we could have more math fun, while at the same time adding optimization!

private boolean isWithin(Coordinate a, Coordinate b, double radius) {

double dlat = Math.abs(a.lat - b.lat),

dlong = Math.abs(a.lng - b.lng);

if (dlat > radius || dlong > radius)

return false;

return (dlat * dlat) + (dlong * dlong) <= radius * radius;

}

Closeness Algorithm

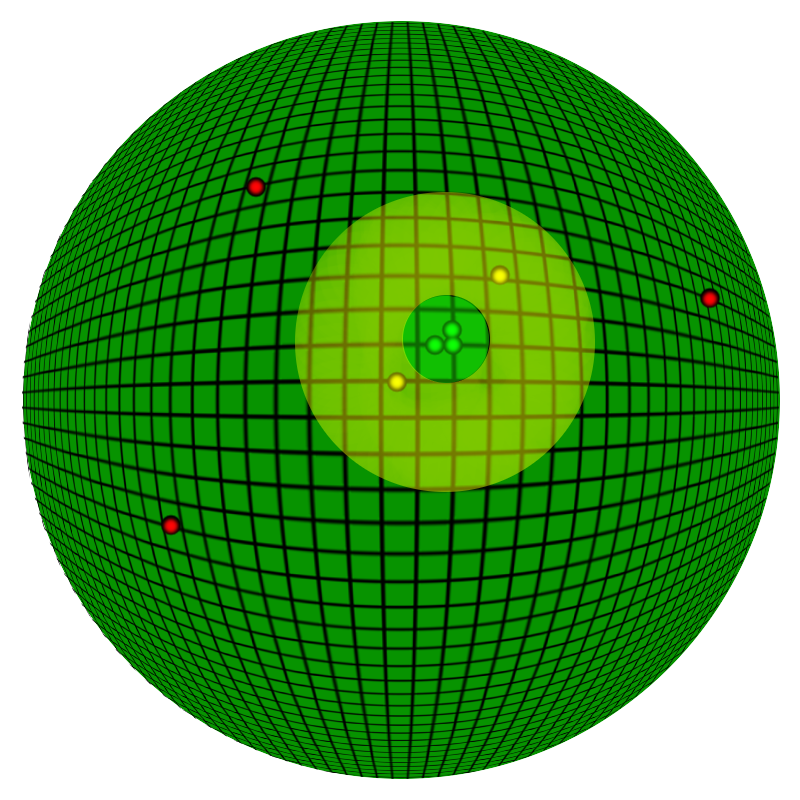

This method effectively draws a circle around our coordinate and asks, is it within that circle? We don’t care what the actual distance is, so long as they are “close enough”. dlat and dlong are the distance between the two points on each axis (Note that it’s still in units of Lat/Long: for example, if you want a match distance of 111.2 meters, you would enter “0.001”).

There are several advantages to this approach. For example, we can then know that, if dx or dy is greater than our “match” distance, that it cannot be inside of our match; this short circuits the algorithm and stops us from having to do the more difficult half the math. As well, since we aren’t interested in distance, but in closeness, we don’t have to bother with converting to meters. As well, we can avoid finding the root of both sides of the equation and save us some more CPU time.

In Summary:

The point of the above example is to really show the difference between usable, meaningful data and data that lacks it. When we started with meaningless data that didn’t represent the value of itself unambiguously, we had no use for it. In fact, we had to spend our efforts getting the data to match more use cases, and code grew as we fought to handle more possibilities.

On the other hand, when data was perfectly represented in the way we stored it, it already handled all use cases. All the hangups we found with strings were eliminated by the use of Doubles. From there, we could focus our efforts on finding new uses and optimizing. In the event you find yourself scrambling to accommodate new use cases, manipulating your data to get more use out of it, ask yourself; “Are we storing this data in a meaningful way?” The answer may be no.

Comments