In a previous article, we described how Serverless architectures enable scalability and can reduce costs. As of now, the most popular cloud provider for Serverless functions is still AWS with its Lambda service.

In this article, I will attempt to demystify the Execution Context of a Lambda invocation and how you can take advantage of it. More specifically for Lambdas written in Java, but this can apply to any language.

Lambda Execution Context

In the AWS Lambda documentation, AWS describes an Execution Context as a “temporary runtime environment that initializes any external dependencies of your Lambda”.

The Execution Context is the invisible stack that AWS creates for your Lambda in order to execute the function. AWS maintains the Context ready to accept new invocations of the function for an unknown amount of time[1] and then deletes it to free up some resource. Between each invocation, AWS freezes and unfreezes the Context.

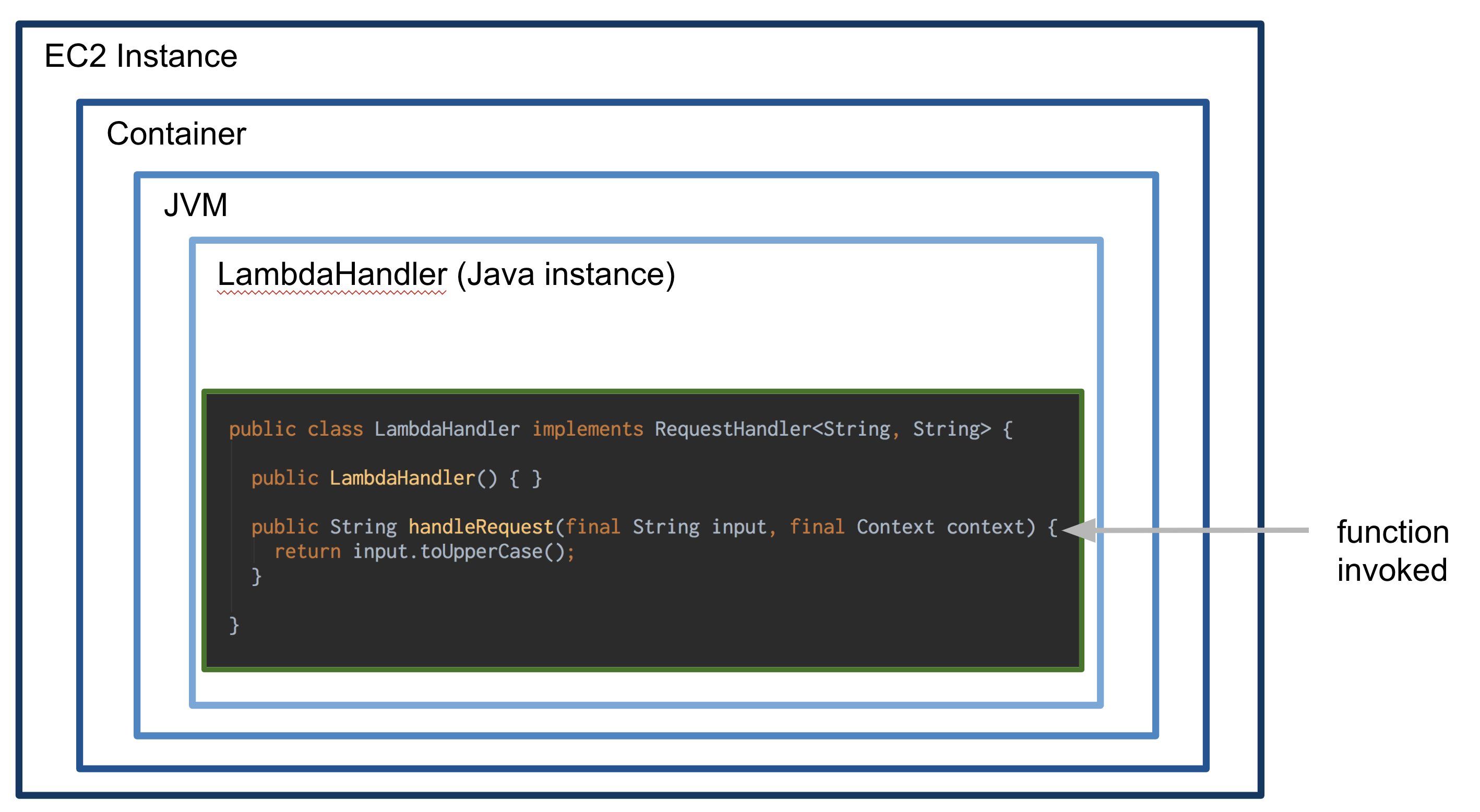

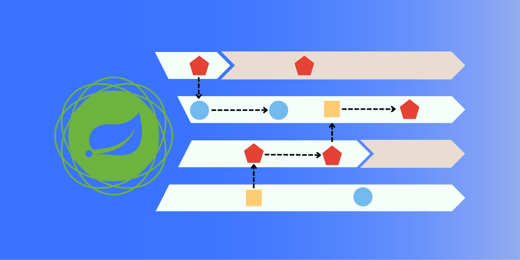

For a Lambda written in Java, this is how I like to represent the different layers of the Execution Context:

- An EC2 instance runs the entire stack. It’s not possible to physically access the instance, and AWS does not share information about this layer

- Container: a container is started to run each Lambda in isolation. Multiple containers run in the same instance

- JVM: For Lambdas written in Java, a Java Virtual Machine is started. AWS uses OpenJDK 8

- An instance of the JavaHandler class where the function is defined

- The function itself

Between each invocation of the handleRequest method, the same Execution Context is reused. This, at least until the Lambda function does not receive requests anymore and AWS destroys the Context to reclaim the resources.

Why it matters

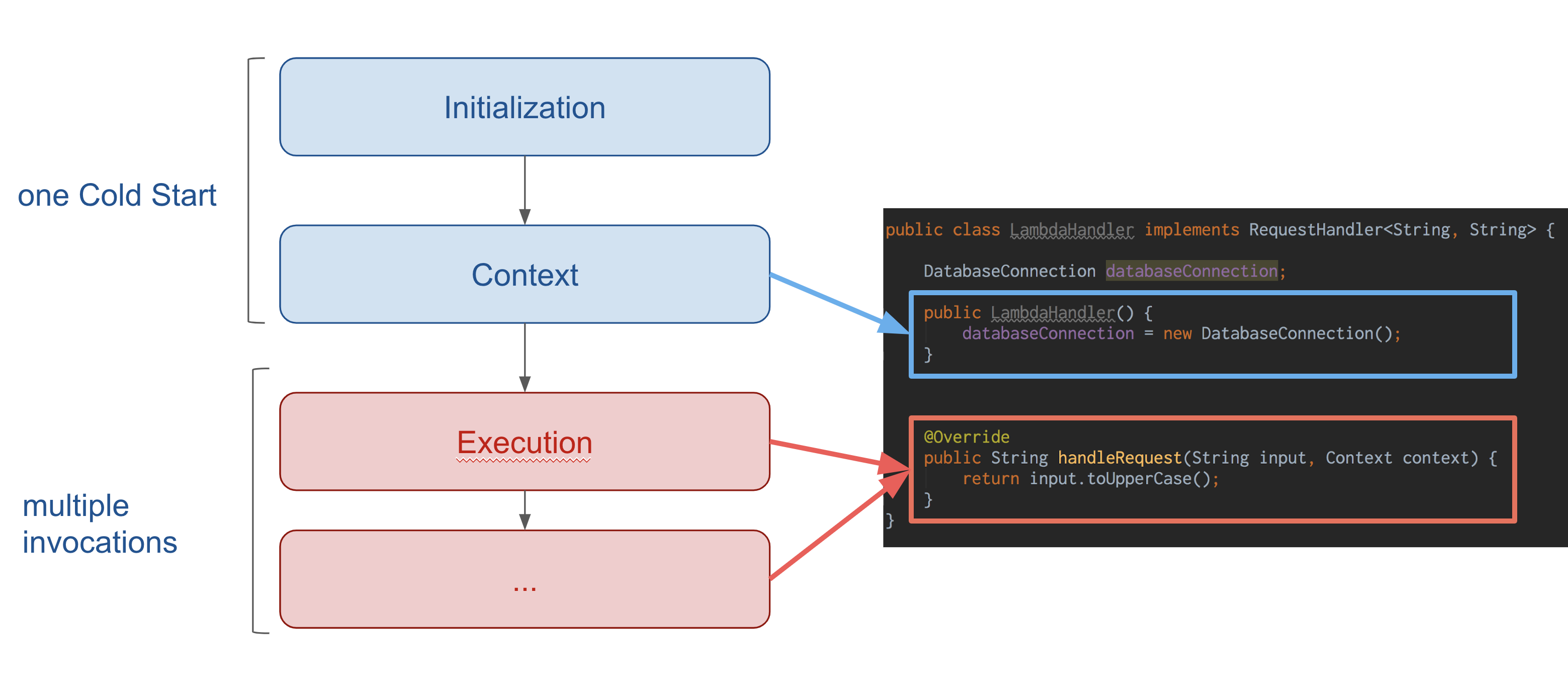

As you can imagine, starting-up the Execution Context can take some time but is inevitable before running the function for the first time.

In the Serverless terminology, this is known as the "cold start". The very first time your Lambda function is invoked, you have to wait for the Execution Context to fully start.

AWS is not billing for this amount of time, but the cold start for the first invocation is an important tradeoff to take into account when using Serverless technologies.

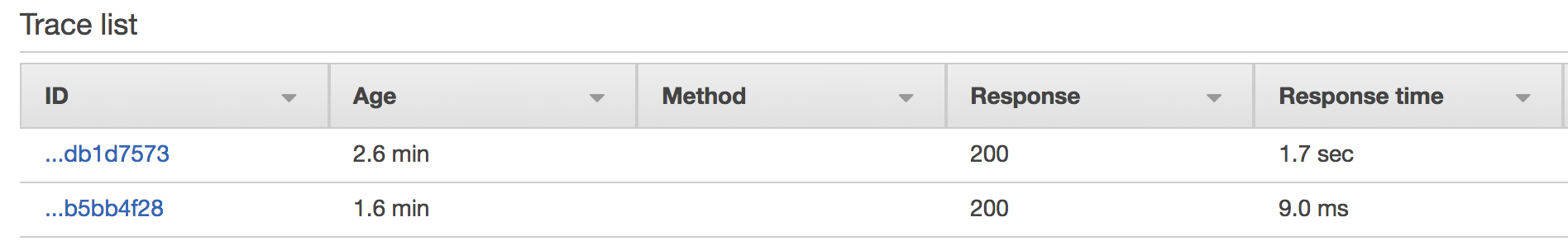

In my test with the code presented in this article, the first invocation took 1.7 seconds to start the Execution Context and the following invocations between 10ms to 30ms.

However, the cold start has a very valuable property: because the Execution Context is reused between invocations, we can keep a reference to the expensive objects created and access them for the future invocations.

Static, Singleton and the Context

Indeed, in the Lambda best practices documentation, one of the best practice actually recommends to take advantage of this Execution Context:

Take advantage of Execution Context reuse to improve the performance of your function. Make sure any externalized configuration or dependencies that your code retrieves are stored and referenced locally after initial execution. Limit the re-initialization of variables/objects on every invocation. Instead use static initialization/constructor, global/static variables and singletons. Keep alive and reuse connections (HTTP, database, etc.) that were established during a previous invocation.

I always found the "static initialization/constructor, global/static variables and singletons" part to be misleading, because static initialization and global variables make it very difficult to write testable code. Instead, I think it should be emphasized that the Class where the function method is running is itself already a Singleton.

Initialize once, reuse every time

For most non-trivial applications, there will always be some "expensive" initializations to perform before a function can run and execute some business logic.

Some of the common tasks are: opening and maintaining a connection to a Database, maintaining an authorization token with another API, creating the AWS clients to access S3/SNS/SQS/..., etc.

For all these initializations, the pattern we have followed in our Lambdas is to execute them in the constructor of the LambdaHandler class and store the objects as instance fields.

By doing this, we effectively treat the LambdaHandler instance as the instance maintaining our application context that can be accessed by all the further function invocations.

Demo

To demonstrate that a field of a Handler class never changes once it is instantiated in the Context, let’s run the following Lambda code. The Lambda generates a random value at various stages in the Java code: a static block (1), the constructor (2) and the invocation method (3).

This Lambda is exposed via AWS API Gateway and gets executed by the following endpoint.

public class LambdaHandler implements RequestHandler<Object, Object> {

static double STATIC_RANDOM;

static {

STATIC_RANDOM = Math.random(); // (1) Value generated in the static block

}

private final double constructorRandom;

public LambdaHandler() {

this.constructorRandom = Math.random(); // (2) Value generated in the LambdaHandler constructor

}

public Object handleRequest(final Object input, final Context context) {

double invocationRandom = Math.random(); // (3) Value generated in the LambdaHandler method for each invocation

String output = String.format(

"{ \"1 - static value\": \"%f\", \" 2 - constructor value\": \"%f\", \"3 - invocation value\": \"%f\"}",

STATIC_RANDOM, this.constructorRandom, invocationRandom);

Map<String, String> headers = new HashMap<>();

headers.put("Content-Type", "application/json");

headers.put("X-Custom-Header", "application/json");

return new GatewayResponse(output, headers, 200);

}

}

- The static block is executed when the Execution Context loads the LambdaHandler class in the JVM for the first time. The random value is stored in a static field.

- The constructor is executed when the Execution Context instantiates a LambdaHandler instance for the first time. The random value is stored in a field of the instance.

- The handleRequest method is executed every time the Lambda function is invoked and the random value stored in a local variable.

Accessing the endpoint multiple times returns the following message:

{ "1 - static value": "0.936418", " 2 - constructor value": "0.400978", "3 - invocation value": "0.362746"}

{ "1 - static value": "0.936418", " 2 - constructor value": "0.400978", "3 - invocation value": "0.969463"}

{ "1 - static value": "0.936418", " 2 - constructor value": "0.400978", "3 - invocation value": "0.0.723602"}

As expected, only the invocation value changes between each invocation. The values generated by both the static block and the constructor remain the same.

If you access the endpoint from your browser multiple times, you will notice the same behavior where only the invocation value changes between your requests. The static and constructor values remain the same. The values will probably be different than the example above, that is because AWS has destroyed the Execution Context and a new one had to get created during your first request.

Note: To deploy this Lambda to your own account, clone the project repository and follow the instructions in the deploy section of the README file.

Conclusion

In this article, we have seen the different layers of the Lambda Execution Context written in Java and how each gets executed during the cold start. Now that we know exactly the different layers, we can take advantage of it to save time during the future invocations of the Lambda.

In the next article, we will see how to apply a manual Dependency Injection pattern to best use the Execution Context while making it more testable.

-

Various benchmarks on internet suggest that AWS maintains the Execution Context of a Java Lambda between 20 and 45 minutes after the last invocations. But AWS does not provide official numbers. ↩︎

Comments